What Is an Automated Sanger Sequencing Read Output Called

Sanger sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing that involves electrophoresis and is based on the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides past Dna polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. Subsequently first being developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977, it became the almost widely used sequencing method for approximately twoscore years. It was first commercialized by Applied Biosystems in 1986. More than recently, higher volume Sanger sequencing has been replaced past next generation sequencing methods, particularly for large-scale, automatic genome analyses. However, the Sanger method remains in wide use for smaller-scale projects and for validation of deep sequencing results. Information technology still has the reward over short-read sequencing technologies (like Illumina) in that it can produce Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence reads of >500 nucleotides and maintains a very low mistake rate with accuracies effectually 99.99%.[1] Sanger sequencing is however actively existence used in efforts for public health initiatives such as sequencing the spike protein from SARS-CoV-two[2] as well as for the surveillance of norovirus outbreaks through the Center for Disease Command and Prevention'southward (CDC) CaliciNet surveillance network.[3]

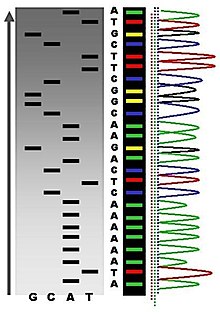

The Sanger (chain-termination) method for DNA sequencing.

Method [edit]

Fluorescent ddNTP molecules

The classical concatenation-termination method requires a unmarried-stranded DNA template, a Dna primer, a Dna polymerase, normal deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and modified di-deoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs), the latter of which terminate Dna strand elongation. These chain-terminating nucleotides lack a 3'-OH group required for the formation of a phosphodiester bail betwixt 2 nucleotides, causing Dna polymerase to cease extension of DNA when a modified ddNTP is incorporated. The ddNTPs may be radioactively or fluorescently labelled for detection in automated sequencing machines.

The Deoxyribonucleic acid sample is divided into four split up sequencing reactions, containing all four of the standard deoxynucleotides (dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP) and the DNA polymerase. To each reaction is added only one of the four dideoxynucleotides (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP), while the other added nucleotides are ordinary ones. The deoxynucleotide concentration should exist approximately 100-fold higher than that of the corresponding dideoxynucleotide (e.thousand. 0.5mM dTTP : 0.005mM ddTTP) to let enough fragments to be produced while still transcribing the complete sequence (but the concentration of ddNTP too depends on the desired length of sequence).[4] Putting it in a more sensible order, 4 separate reactions are needed in this process to exam all iv ddNTPs. Following rounds of template DNA extension from the spring primer, the resulting DNA fragments are heat denatured and separated by size using gel electrophoresis. In the original publication of 1977,[4] the formation of base-paired loops of ssDNA was a cause of serious difficulty in resolving bands at some locations. This is oft performed using a denaturing polyacrylamide-urea gel with each of the four reactions run in one of iv individual lanes (lanes A, T, 1000, C). The DNA bands may so be visualized past autoradiography or UV light, and the Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence can be directly read off the X-ray film or gel image.

Office of a radioactively labelled sequencing gel

In the image on the correct, 10-ray film was exposed to the gel, and the dark bands correspond to DNA fragments of different lengths. A dark ring in a lane indicates a DNA fragment that is the result of chain termination later on incorporation of a dideoxynucleotide (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP). The relative positions of the dissimilar bands among the four lanes, from bottom to elevation, are so used to read the Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence.

Deoxyribonucleic acid fragments are labelled with a radioactive or fluorescent tag on the primer (one), in the new Deoxyribonucleic acid strand with a labeled dNTP, or with a labeled ddNTP.

Technical variations of chain-termination sequencing include tagging with nucleotides containing radioactive phosphorus for radiolabelling, or using a primer labeled at the 5' cease with a fluorescent dye. Dye-primer sequencing facilitates reading in an optical system for faster and more than economical assay and automation. The later development by Leroy Hood and coworkers[5] [vi] of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and primers set the phase for automatic, high-throughput Dna sequencing.

Sequence ladder by radioactive sequencing compared to fluorescent peaks

Chain-termination methods have greatly simplified DNA sequencing. For instance, chain-termination-based kits are commercially available that contain the reagents needed for sequencing, pre-aliquoted and ready to utilize. Limitations include non-specific bounden of the primer to the Deoxyribonucleic acid, affecting accurate read-out of the Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence, and DNA secondary structures affecting the fidelity of the sequence.

Dye-terminator sequencing [edit]

Capillary electrophoresis

Dye-terminator sequencing utilizes labelling of the concatenation terminator ddNTPs, which permits sequencing in a unmarried reaction rather than four reactions as in the labelled-primer method. In dye-terminator sequencing, each of the four dideoxynucleotide chain terminators is labelled with fluorescent dyes, each of which emits light at different wavelengths.

Owing to its greater expediency and speed, dye-terminator sequencing is at present the mainstay in automated sequencing. Its limitations include dye effects due to differences in the incorporation of the dye-labelled chain terminators into the Deoxyribonucleic acid fragment, resulting in unequal peak heights and shapes in the electronic Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence trace chromatogram after capillary electrophoresis (see figure to the left).

This trouble has been addressed with the use of modified Dna polymerase enzyme systems and dyes that minimize incorporation variability, too every bit methods for eliminating "dye blobs". The dye-terminator sequencing method, along with automatic high-throughput DNA sequence analyzers, was used for the vast majority of sequencing projects until the introduction of adjacent generation sequencing.

Automation and sample training [edit]

View of the start of an example dye-terminator read

Automated DNA-sequencing instruments (Dna sequencers) can sequence up to 384 Deoxyribonucleic acid samples in a single batch. Batch runs may occur up to 24 times a day. DNA sequencers split up strands by size (or length) using capillary electrophoresis, they discover and record dye fluorescence, and output data as fluorescent superlative trace chromatograms. Sequencing reactions (thermocycling and labelling), cleanup and re-break of samples in a buffer solution are performed separately, before loading samples onto the sequencer. A number of commercial and not-commercial software packages can trim low-quality Deoxyribonucleic acid traces automatically. These programs score the quality of each peak and remove low-quality base peaks (which are generally located at the ends of the sequence). The accuracy of such algorithms is inferior to visual exam by a human operator, but is acceptable for automated processing of large sequence information sets.

Applications of Dye-terminating Sequencing [edit]

The field of Public Health plays many roles to back up patient diagnostics too as environmental surveillance of potential toxic substances and circulating biological pathogens. Public Wellness Laboratories (PHL) and other laboratories around the world take played a pivotal part in providing rapid sequencing data for the surveillance of the virus SARS-CoV-2, causative agent for COVID-nineteen, during the pandemic that was alleged a public health emergency on January 30, 2020.[seven] Laboratories were tasked with the rapid implementation of sequencing methods and asked to provide accurate data to assist in the decision-making models for the development of policies to mitigate spread of the virus. Many laboratories resorted to next generation sequencing methodologies while others supported efforts with Sanger sequencing. The sequencing efforts of SARS-CoV-2 are many, while most laboratories implemented whole genome sequencing of the virus, others accept opted to sequence very specific genes of the virus such equally the Southward-gene, encoding the information needed to produce the spike protein. The loftier mutation rate of SARS-CoV-ii leads to genetic differences within the South-gene and these differences have played a part in the infectivity of the virus.[8] Sanger sequencing of the South-factor provides a quick, accurate, and more affordable method to retrieving the genetic code. Laboratories in lower income countries may not have the capabilities to implement expensive applications such as side by side generation sequencing, so Sanger methods may prevail in supporting the generation of sequencing data for surveillance of variants.

Sanger sequencing is also the "gilt standard" for norovirus surveillance methods for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) CaliciNet network. CalciNet is an outbreak surveillance network that was established in March 2009. The goal of the network is to collect sequencing data of circulating noroviruses in the Usa and activate downstream action to determine the source of infection to mitigate the spread of the virus. The CalciNet network has identified many infections every bit foodborne illnesses.[ix] This information can then exist published and used to develop recommendations for hereafter action to preclude tainting food. The methods employed for detection of norovirus involve targeted amplification of specific areas of the genome. The amplicons are then sequenced using dye-terminating Sanger sequencing and the chromatograms and sequences generated are analyzed with a software parcel developed in BioNumerics. Sequences are tracked and strain relatedness is studied to infer epidemiological relevance.

Challenges [edit]

Mutual challenges of DNA sequencing with the Sanger method include poor quality in the first xv-forty bases of the sequence due to primer binding and deteriorating quality of sequencing traces after 700-900 bases. Base calling software such as Phred typically provides an estimate of quality to aid in trimming of depression-quality regions of sequences.[10] [11]

In cases where DNA fragments are cloned before sequencing, the resulting sequence may comprise parts of the cloning vector. In contrast, PCR-based cloning and side by side-generation sequencing technologies based on pyrosequencing often avoid using cloning vectors. Recently, one-step Sanger sequencing (combined amplification and sequencing) methods such as Ampliseq and SeqSharp accept been developed that let rapid sequencing of target genes without cloning or prior amplification.[12] [thirteen]

Current methods tin directly sequence only relatively curt (300-thou nucleotides long) DNA fragments in a single reaction. The main obstacle to sequencing DNA fragments higher up this size limit is insufficient power of separation for resolving large DNA fragments that differ in length by only one nucleotide.

Microfluidic Sanger sequencing [edit]

Microfluidic Sanger sequencing is a lab-on-a-chip application for DNA sequencing, in which the Sanger sequencing steps (thermal cycling, sample purification, and capillary electrophoresis) are integrated on a wafer-scale flake using nanoliter-scale sample volumes. This applied science generates long and authentic sequence reads, while obviating many of the significant shortcomings of the conventional Sanger method (eastward.g. loftier consumption of expensive reagents, reliance on expensive equipment, personnel-intensive manipulations, etc.) by integrating and automating the Sanger sequencing steps.

In its modernistic inception, high-throughput genome sequencing involves fragmenting the genome into pocket-sized single-stranded pieces, followed by amplification of the fragments by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Adopting the Sanger method, each Dna fragment is irreversibly terminated with the incorporation of a fluorescently labeled dideoxy concatenation-terminating nucleotide, thereby producing a DNA "ladder" of fragments that each differ in length by one base of operations and bear a base-specific fluorescent label at the terminal base of operations. Amplified base ladders are then separated by capillary array electrophoresis (CAE) with automated, in situ "finish-line" detection of the fluorescently labeled ssDNA fragments, which provides an ordered sequence of the fragments. These sequence reads are then reckoner assembled into overlapping or face-to-face sequences (termed "contigs") which resemble the full genomic sequence once fully assembled.[14]

Sanger methods achieve read lengths of approximately 800bp (typically 500-600bp with non-enriched Dna). The longer read lengths in Sanger methods display significant advantages over other sequencing methods especially in terms of sequencing repetitive regions of the genome. A claiming of short-read sequence data is particularly an issue in sequencing new genomes (de novo) and in sequencing highly rearranged genome segments, typically those seen of cancer genomes or in regions of chromosomes that exhibit structural variation.[15]

Applications of microfluidic sequencing technologies [edit]

Other useful applications of DNA sequencing include single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection, single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) heteroduplex analysis, and brusk tandem echo (STR) analysis. Resolving DNA fragments according to differences in size and/or conformation is the well-nigh critical stride in studying these features of the genome.[fourteen]

Device design [edit]

The sequencing chip has a four-layer construction, consisting of 3 100-mm-diameter glass wafers (on which device elements are microfabricated) and a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane. Reaction chambers and capillary electrophoresis channels are etched between the top two glass wafers, which are thermally bonded. Three-dimensional aqueduct interconnections and microvalves are formed by the PDMS and bottom manifold glass wafer.

The device consists of three functional units, each corresponding to the Sanger sequencing steps. The thermal cycling (TC) unit is a 250-nanoliter reaction chamber with integrated resistive temperature detector, microvalves, and a surface heater. Move of reagent between the top all-drinking glass layer and the lower glass-PDMS layer occurs through 500-μm-diameter via-holes. After thermal-cycling, the reaction mixture undergoes purification in the capture/purification chamber, and then is injected into the capillary electrophoresis (CE) bedroom. The CE unit consists of a xxx-cm capillary which is folded into a compact switchback pattern via 65-μm-wide turns.

Sequencing chemistry [edit]

- Thermal cycling

- In the TC reaction bedchamber, dye-terminator sequencing reagent, template DNA, and primers are loaded into the TC chamber and thermal-cycled for 35 cycles ( at 95 °C for 12 seconds and at threescore °C for 55 seconds).

- Purification

- The charged reaction mixture (containing extension fragments, template Deoxyribonucleic acid, and excess sequencing reagent) is conducted through a capture/purification sleeping accommodation at thirty °C via a 33-Volts/cm electric field applied betwixt capture outlet and inlet ports. The capture gel through which the sample is driven, consists of 40 μM of oligonucleotide (complementary to the primers) covalently leap to a polyacrylamide matrix. Extension fragments are immobilized by the gel matrix, and excess primer, template, free nucleotides, and salts are eluted through the capture waste port. The capture gel is heated to 67-75 °C to release extension fragments.

- Capillary electrophoresis

- Extension fragments are injected into the CE chamber where they are electrophoresed through a 125-167-Five/cm field.

Platforms [edit]

The Apollo 100 platform (Microchip Biotechnologies Inc., Dublin, CA)[xvi] integrates the offset two Sanger sequencing steps (thermal cycling and purification) in a fully automated organisation. The manufacturer claims that samples are ready for capillary electrophoresis inside three hours of the sample and reagents being loaded into the system. The Apollo 100 platform requires sub-microliter volumes of reagents.

Comparisons to other sequencing techniques [edit]

| Technology | Number of lanes | Injection volume (nL) | Analysis time | Average read length | Throughput (including analysis; Mb/h) | Gel pouring | Lane tracking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slab gel | 96 | 500–1000 | six–8 hours | 700 bp | 0.0672 | Aye | Yep |

| Capillary array electrophoresis | 96 | 1–5 | 1–three hours | 700 bp | 0.166 | No | No |

| Microchip | 96 | 0.one–0.5 | half-dozen–30 minutes | 430 bp | 0.660 | No | No |

| 454/Roche FLX (2008) | < 0.001 | 4 hours | 200–300 bp | 20–30 | |||

| Illumina/Solexa (2008) | 2–3 days | 30–100 bp | 20 | ||||

| ABI/SOLiD (2008) | 8 days | 35 bp | five–15 | ||||

| Illumina MiSeq (2019) | i–three days | 2x75–2x300 bp | 170–250 | ||||

| Illumina NovaSeq (2019) | 1–two days | 2x50–2x150 bp | 22,000–67,000 | ||||

| Ion Torrent Ion 530 (2019) | 2.five–4 hours | 200–600 bp | 110–920 | ||||

| BGI MGISEQ-T7 (2019) | one day | 2x150 bp | 250,000 | ||||

| Pacific Biosciences SMRT (2019) | 10–xx hours | x–thirty kb | one,300 | ||||

| Oxford Nanopore MinIon (2019) | 3 days | xiii–twenty kb[19] | 700 |

The ultimate goal of high-throughput sequencing is to develop systems that are low-cost, and extremely efficient at obtaining extended (longer) read lengths. Longer read lengths of each single electrophoretic separation, substantially reduces the toll associated with de novo Dna sequencing and the number of templates needed to sequence Deoxyribonucleic acid contigs at a given redundancy. Microfluidics may allow for faster, cheaper and easier sequence associates.[14]

References [edit]

- ^ Shendure J, Ji H (October 2008). "Side by side-generation Deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing". Nature Biotechnology. 26 (10): 1135–1145. doi:10.1038/nbt1486. PMID 18846087. S2CID 6384349.

- ^ Daniels RS, Harvey R, Ermetal B, Xiang Z, Galiano M, Adams L, McCauley JW (November 2021). "A Sanger sequencing protocol for SARS-CoV-2 S-gene". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 15 (6): 707–710. doi:ten.1111/irv.12892. PMC8447197. PMID 34346163.

- ^ Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Williams K, Lee D, Vinjé J (August 2011). "Novel surveillance network for norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks, U.s.a.". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1389–1395. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101837. PMC3381557. PMID 21801614.

- ^ a b Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (December 1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (12): 5463–5467. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC431765. PMID 271968.

- ^ Smith LM, Sanders JZ, Kaiser RJ, Hughes P, Dodd C, Connell CR, et al. (1986). "Fluorescence detection in automatic Dna sequence analysis". Nature. 321 (6071): 674–679. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..674S. doi:ten.1038/321674a0. PMID 3713851. S2CID 27800972.

We take developed a method for the fractional automation of Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence analysis. Fluorescence detection of the Deoxyribonucleic acid fragments is accomplished past means of a fluorophore covalently attached to the oligonucleotide primer used in enzymatic Dna sequence analysis. A different coloured fluorophore is used for each of the reactions specific for the bases A, C, G and T. The reaction mixtures are combined and co-electrophoresed downwards a single polyacrylamide gel tube, the separated fluorescent bands of Dna are detected near the lesser of the tube, and the sequence data is acquired direct by estimator.

- ^ Smith LM, Fung S, Hunkapiller MW, Hunkapiller TJ, Hood LE (April 1985). "The synthesis of oligonucleotides containing an aliphatic amino group at the 5' terminus: synthesis of fluorescent Deoxyribonucleic acid primers for use in Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. thirteen (seven): 2399–2412. doi:10.1093/nar/13.vii.2399. PMC341163. PMID 4000959.

- ^ Taylor DB (2021-03-17). "A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-12-05 .

- ^ Sanches PR, Charlie-Silva I, Braz HL, Bittar C, Freitas Calmon M, Rahal P, Cilli EM (September 2021). "Recent advances in SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and RBD mutations comparing between new variants Alpha (B.1.1.7, United Kingdom), Beta (B.1.351, South Africa), Gamma (P.1, Brazil) and Delta (B.ane.617.two, India)". Journal of Virus Eradication. 7 (3): 100054. doi:ten.1016/j.jve.2021.100054. PMC8443533. PMID 34548928.

- ^ Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Williams K, Lee D, Vinjé J (August 2011). "Novel surveillance network for norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1389–1395. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101837. PMC3381557. PMID 21801614.

- ^ "Phred - Quality Base Calling". Retrieved 2011-02-24 .

- ^ Ledergerber C, Dessimoz C (September 2011). "Base of operations-calling for next-generation sequencing platforms". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 12 (5): 489–497. doi:10.1093/bib/bbq077. PMC3178052. PMID 21245079.

- ^ Murphy KM, Berg KD, Eshleman JR (January 2005). "Sequencing of genomic Deoxyribonucleic acid past combined distension and cycle sequencing reaction". Clinical Chemistry. 51 (ane): 35–39. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.039164. PMID 15514094.

- ^ SenGupta DJ, Cookson BT (May 2010). "SeqSharp: A general approach for improving cycle-sequencing that facilitates a robust ane-step combined amplification and sequencing method". The Periodical of Molecular Diagnostics. 12 (three): 272–277. doi:ten.2353/jmoldx.2010.090134. PMC2860461. PMID 20203000.

- ^ a b c Kan CW, Fredlake CP, Doherty EA, Barron AE (Nov 2004). "DNA sequencing and genotyping in miniaturized electrophoresis systems". Electrophoresis. 25 (21–22): 3564–3588. doi:ten.1002/elps.200406161. PMID 15565709. S2CID 4851728.

- ^ a b Morozova O, Marra MA (Nov 2008). "Applications of next-generation sequencing technologies in functional genomics". Genomics. 92 (5): 255–264. doi:x.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.001. PMID 18703132.

- ^ Microchip Biologies Inc. Apollo 100

- ^ Sinville R, Soper SA (July 2007). "High resolution Dna separations using microchip electrophoresis". Journal of Separation Science. thirty (11): 1714–1728. doi:10.1002/jssc.200700150. PMID 17623451.

- ^ Kumar KR, Cowley MJ, Davis RL (October 2019). "Adjacent-Generation Sequencing and Emerging Technologies". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 45 (7): 661–673. doi:10.1055/southward-0039-1688446. PMID 31096307.

- ^ Tyson JR, O'Neil NJ, Jain M, Olsen HE, Hieter P, Snutch TP (Feb 2018). "MinION-based long-read sequencing and associates extends the Caenorhabditis elegans reference genome". Genome Research. 28 (2): 266–274. doi:10.1101/gr.221184.117. PMC5793790. PMID 29273626.

Further reading [edit]

- Dewey Iron, Pan Southward, Wheeler MT, Quake SR, Ashley EA (Feb 2012). "Dna sequencing: clinical applications of new DNA sequencing technologies". Circulation. 125 (7): 931–944. doi:ten.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972828. PMC3364518. PMID 22354974.

- Sanger F, Coulson AR, Barrell BG, Smith AJ, Roe BA (October 1980). "Cloning in unmarried-stranded bacteriophage as an aid to rapid DNA sequencing". Journal of Molecular Biological science. 143 (ii): 161–178. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(80)90196-5. PMID 6260957.

External links [edit]

- MBI Says New Tool That Automates Sanger Sample Prep Cuts Reagent and Labor Costs

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanger_sequencing

0 Response to "What Is an Automated Sanger Sequencing Read Output Called"

Post a Comment